Telephone

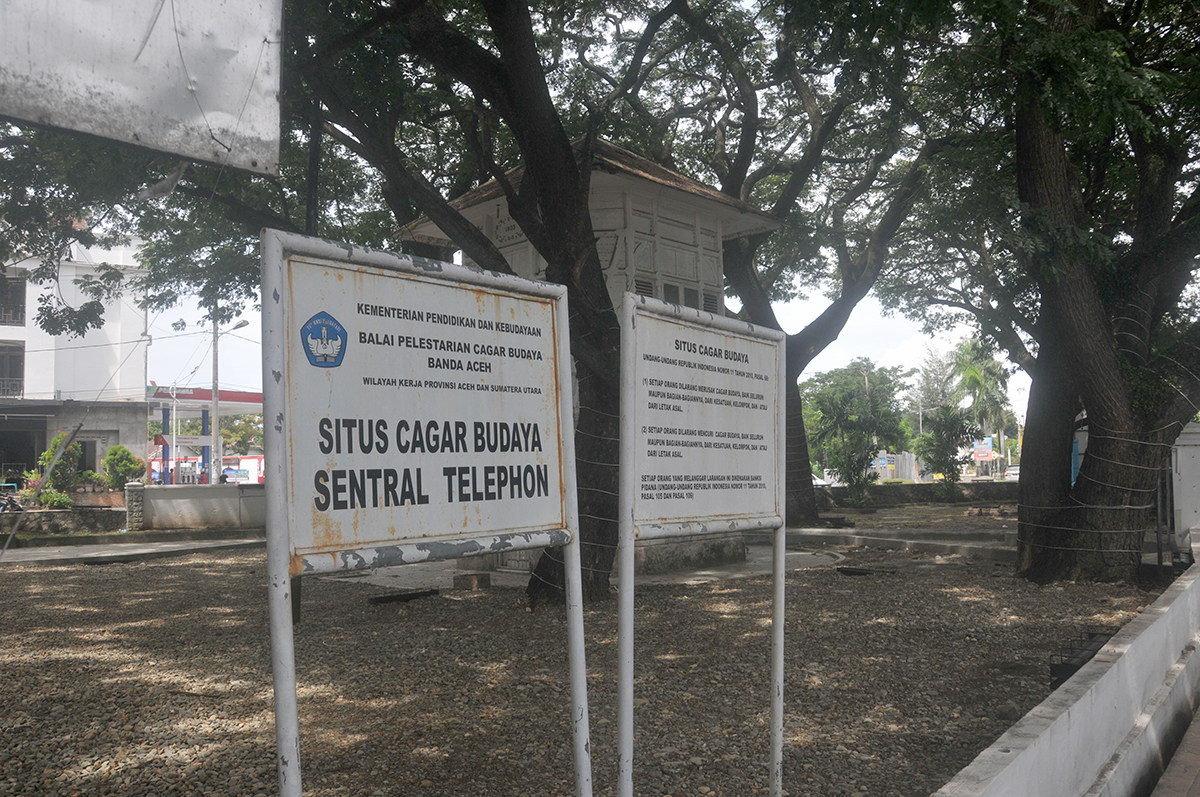

In 1903, all army posts on the Acehnese west coast were connected to a telephone line to the main base here in Koetaradja. From then on, reinforcements could be called for day and night in case of an emergency. The small white tower we're currently looking at used to be the end of this west coast telephone line.

On the top floor, the operator used to work. Downstairs, officers could deliver messages or make calls. The Acehnese west coast remained a very unsafe area well into the 20th century.

Acehnese surprise attacks were met with Dutch responses. Hendrik Colijn, who later would become Prime Minister of the Netherlands, used this telephone office very often as he was stationed on the west coast for many years. In a letter to his wife, he described his work.

When things finally settled down a bit in Aceh in the 1930s, non-military people were also allowed to use the telephone line. In Dutch archives, several Acehnese phone directories from those days have been saved, which give a fascinating insight into the colonial society in Koetaradja. The phone directories consisted of only a few pages.

A phone connection was so expensive that only a couple of people could afford it. The first page gives advice on proper telephone use. Users are advised not to use the phone when there is a thunderstorm.

Also, cursing, unpleasant, or rough language towards the Koetaradja operator was not permitted. The 1932 directory lists several civilian connections in Koetaradja. Amongst others, automobile shop Kolkenko, Ms. Huestra's flower stall, Dr. Van Bommel, specialized in internal diseases, high school teacher Ms. Huizing, Catholic Priest Van Vandersanden, also available at night in case of emergency.

Today, it is difficult to imagine that all those people once lived in this city and called each other using this little telephone office in the middle of this now very busy traffic intersection. Presently, the building is used by the Indonesian Soccer Federation. Upstairs is an office. Downstairs, people are usually playing cards or dominoes. They are very friendly. If you like, you can ask to have a look inside.

%20copy.jpg)